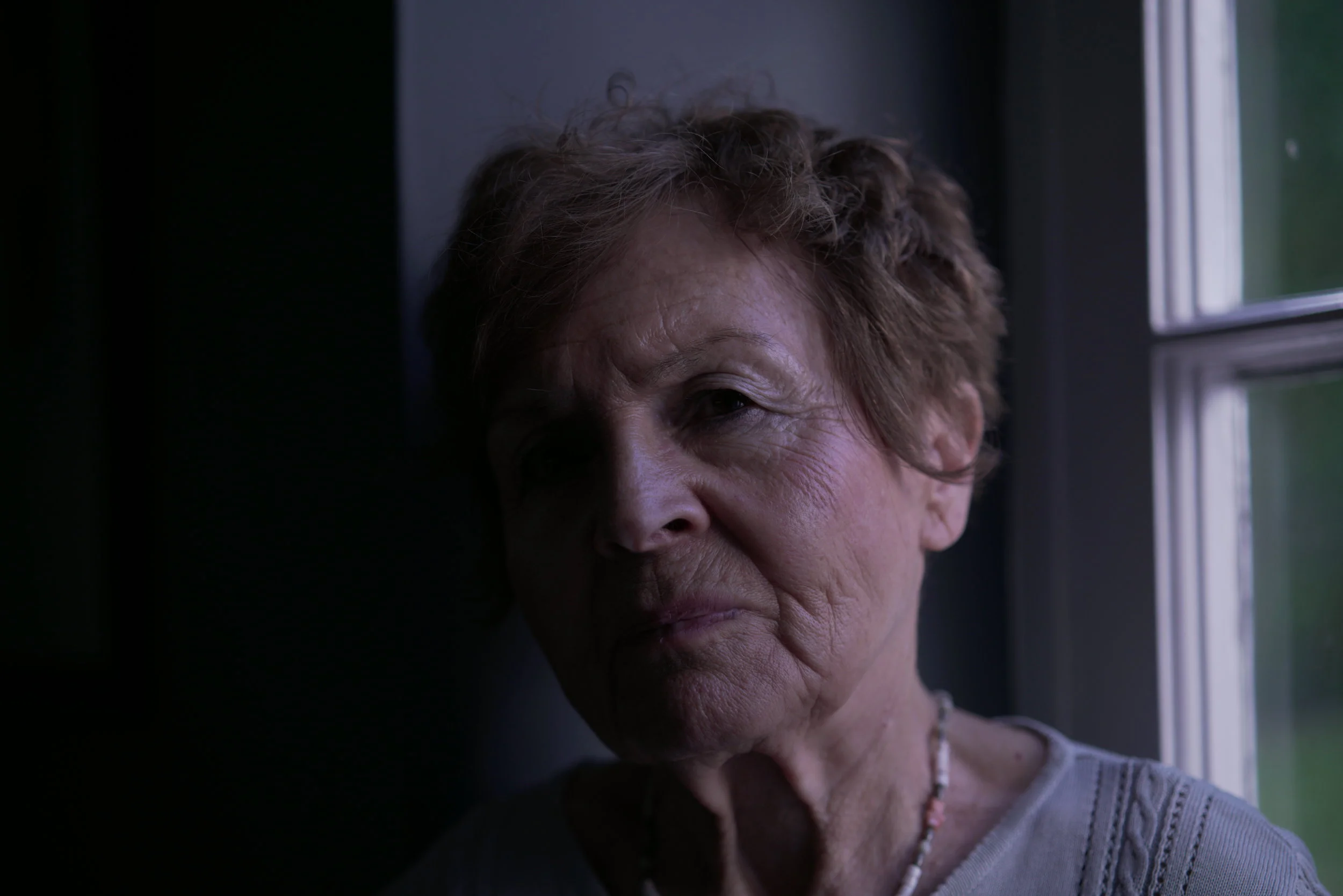

He hid me, Aunt Rouja, Uncle Selig and 11 other Jews on the estate. At first we stayed in some horse stables but remaining above ground was too risky. So, Edek helped us dig an underground bunker, where we lived in very poor and cramped conditions. I remember, there was an electric bulb and a bucket, but very little food, just bread and onions. I stayed in that hole for nearly a year, without leaving once. No fresh air, no daylight.

Finally, Aunt Rouja felt that the only way to preserve my health was to get me out. Remember, I was still only 11. So, by changing my name, my aunt managed to obtain some false papers for me. I had to learn every detail of my new identity - as a young Catholic girl whose parents had been killed. And although I looked incredibly ill, I managed to find my way to Krakow, another city in Poland, where I was admitted to a convent.

Despite the hardships I endured, I was one of the few lucky ones. However for me, luck played only a small part in my survival. More than anything, I owe the fact that I managed to stay alive to the heroism of the young man who saved me and thirteen other Jews: Edek. Don't forget, if he had been caught hiding us, he would have been executed, so his bravery is almost unimaginable.

If only I knew his last name. Because Edek is a common name in Poland, much like Edward in English. And although I have tried over the years to find him, my search has proved fruitless.

Yet now, with the launch of this new film, we're going to try again.

To protect my new identity, I learned to sing Christian hymns and recite Christian prayers. From there I was moved, along with three other girls, to live with a priest, before finally going to live with an elderly couple. There, I worked as a maid until Krakow was liberated in early 1945, when I was 13.